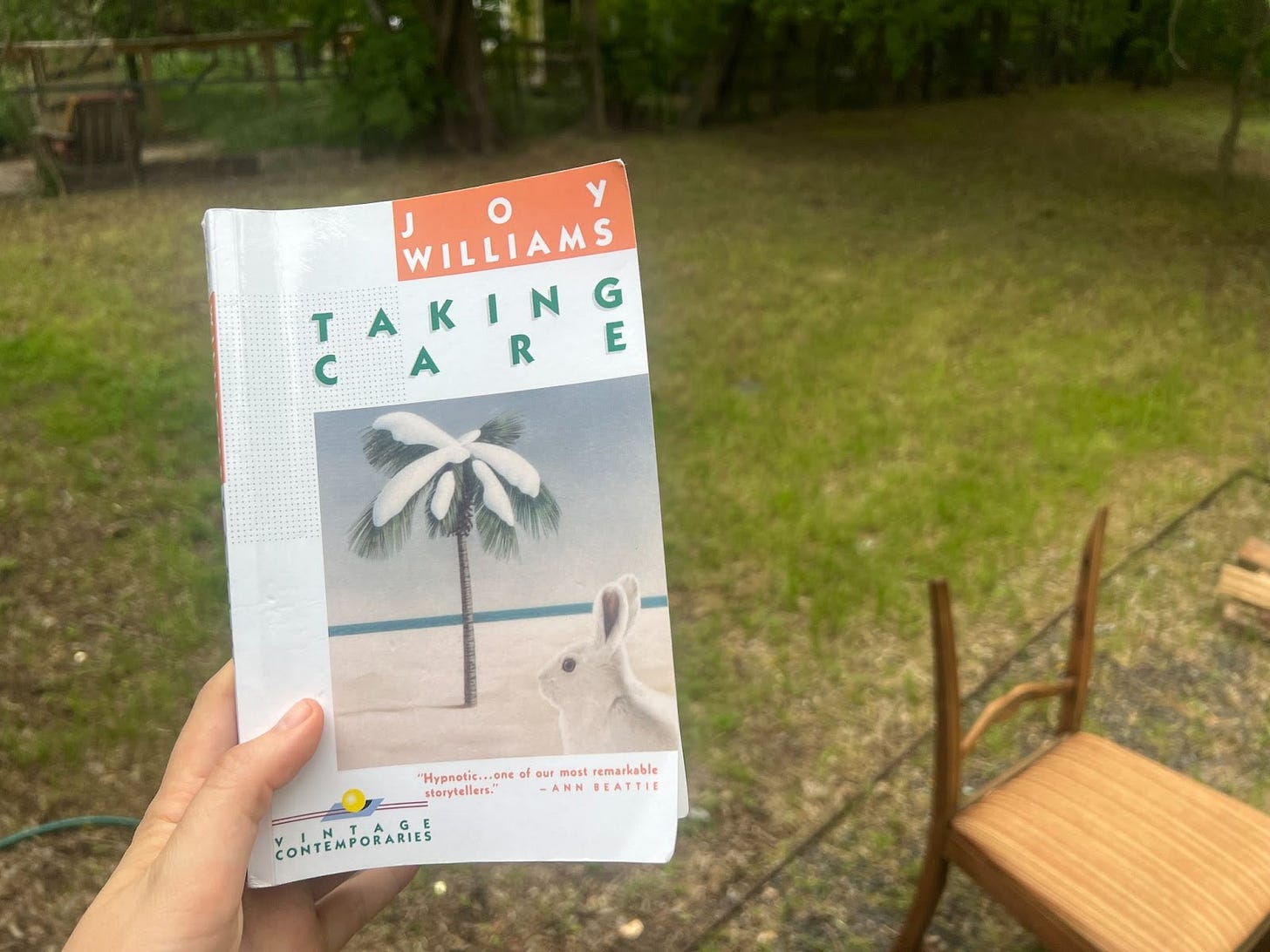

I took Taking Care, the short story collection by Joy Williams, on a weekend road trip to West Texas. I’ve learned that it's good to have a few stories up your sleeve when on a group trip. But in this case, I planned to use this book as a crutch after I took a bad spill at a party the week before.

In Marfa, I wore a thick velcro boot to protect my ankle. The boot made me feel like a Joy Williams character: burdened, strange, and unsexy. This is not how one hopes to feel on a couples road trip...

Instead of orange groves and sea cranes, I was hobbling past Donald Judd sculpture and desert birds: buzzards sunning their black wings over crumbling chapels, road runners, conspiring crows.

On the first day, unable to enjoy a morning walk, I read the first couple of Williams’ stories alone, next to a cactus. Taking in the dry air and feeling slightly enfeebled, I felt like a patient of the desert, sent there to either convalesce or make peace with the inevitable. But after a while, the dramatics faded. The stars demand silence and attention out there. There’s a scary sort of magic to it. My experience of their clarity seemed to fix things.

I stopped considering myself an incapable invalid and started recognizing myself as an invalid capable having a good time. We stayed occupied with the best sandwiches I’ve ever had, a trip to the McDonald Observatory, and cheap Coronas at the townie bar which knew to rev the locals up with NIN and Disturbed.

I finished the rest of the book back home.

This collection of stories was published as a Vintage Contemporaries Edition in 1985, but many of the stories were published in Esquire much earlier. Now 81, Williams was married to the magazine’s fiction editor, Rust Hills, for 34 years before his death. I think she would’ve been a success anyway. But I am curious about the ways the couple inspired each other. (More on this later…)

In Taking Care, Joy Williams’ characters are difficult people who are suppressing something, usually desire and death. Animals are often a proxy for these feelings, collateral damage for people’s anxieties and objects for casual cruelty. There’s Jane and Jackson’s dog in Preparation for a Collie, under threat as a result of the complications of family life. The couple is obsessed with getting rid of him. They drink heavily as they wait for life to feel better. The hungry dog sheds. Their sensitive son David, who loves the dog, is an embarrassment to his mother.

The dog has basic needs, which remind the couple of their own unhappiness. They say they want to get rid of the dog to “simplify their life.”

I won’t spoil it, but the end of the story is revealing in its severity towards the animal. And we know the owner's problems aren’t really ever about the dog in the first place from the first two lines.

“There is Jane and there is Jackson and there is David.

There is the dog.”

In positioning the animal as secondary, Williams invites the reader to question her character's desire to shed the dog, and to probe into what they’re really about. She also raises questions about our relationship to animals—and small children— as stewards over innocents who can’t speak for themselves. Why must they suffer the worst of us? How do we project ourselves onto their world? And what responsibility do we have to them?

I think about this while walking around Austin, surrounded by neurotics with pets. I love dogs, and hope to adopt one someday, but I am annoyed by the sheer numbers I see misbehaving in coffee shops, parks, and bars while their owners scroll their phones. I worry that many people have them as a predetermined accessory to their lifestyle, so they have something to talk about on Hinge, or worse, to fill a human void. In doing so, they ask their dog to remedy problems that they could never possibly fix. In some ways, we all do this. If not to our own dogs, we demand things from the birds in our backyard and the buzzards on our road trips. We ask them to witness us without giving much in return, while passively destroying their environments.

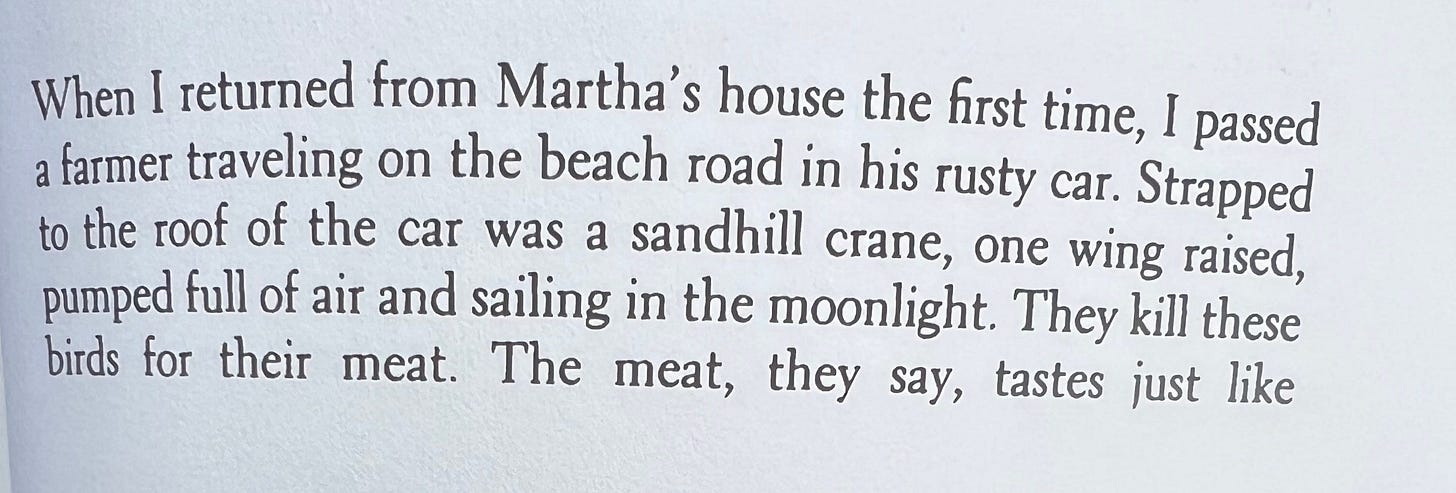

For Williams, environmentalism is more overtly apparent in The Quick and The Dead, through the monologues of Alice and her grandparents, but her passion for all types of life runs through these fictions. Elsewhere in this collection, there’s mention of seabirds killed for their meat and overfished tarpon you never see anymore. In Building, there’s an illegal toucan and a turkey spared from Thanksgiving, both destined to endure the narrator’s respective marriages. I haven’t read much else by Williams, but I’m interested in her other non-fiction work. Especially, her 1987 guidebook on The Florida Keys, a poetic Florida-vibes handbook which discusses the state’s imperiled terrain at length. With new EPA deregulation, rising sea levels, and ongoing population growth, this is obviously still a concern. Though today, despite increased awareness, I’m not sure if this is the main thing on everyone’s minds.

In Taking Care, the story, we finally meet William’s hero, her earthly steward: Jones.

Jones is a preacher with a sick wife in the hospital. He recently has become the caretaker of his baby granddaughter. Out on an ecstatic drive, alone with the baby, they spot a white snowshoe rabbit:

“Jones, driving, feels almost gay. The snow is so beautiful. Everything is white. Jones is an educated man. He has read Melville, who says that white is the colorless all-color of atheism from which we shrink. Jones does not believe this. He sees a holiness in snow, a promise. He hopes that his wife will know that it is snowing even though she is separated from the window by a curtain. Jones sees something moving across the snow, a part of the snow itself, running. Although he is going slowly, he takes his foot off the accelerator. ‘Look darling, a snowshoe rabbit.’ At the sound of his voice, the baby stretches open her mouth and narrows her eyes in soundless glee.”

In this case, the animal acts as a vessel for hope and the possibility of new beginnings in the face of mortality. This is a strangely joyous juncture, enabled by the injection of new life (his granddaughter) into his fading one.

Now back to the question of Joy William’s and her husband, Rust Hills.

Joy and Rust. Writer and editor. Young and old.

Twenty years her senior, he’s essentially her Jungian shadow, if only in this brief biography. As a younger writer, she represents life and creation. He’s life on its way out, always narrowing.

Joy is a roadside sign advertising “ice cream in 1 mile” and the resulting cone of soft-serve; Rust is that same sign 30 years later, when all that’s left at the destination is a parking lot.

Maybe it’s a silly semantic connection to make here, but this attraction to the polarities of the human condition fills her writing. Throughout Taking Care, she works the balance beam between opposites: birth and death, snow and swamp, growth and destruction. Her vision is often concerned with the people dwelling in the languid landscape of her home state, Florida: an environment in constant bloom and decay. But when they’re not obviously in Florida, the environments are usually “fragrant with ice.”

Her fascination with opposites and innocents could be why she loves to put babies in the laps of the dying, like the preacher who adopts his baby granddaughter in Taking Care, and the childless octogenarian sisters who find a newborn hanging from their mailbox in Traveling to Pridesup.

Just before Otila, the most childlike of the old sisters, finds the baby, the liveliness of her surroundings stirs a mostly dormant feeling: joy.

“She could see the bass shaking the surface of the water and she felt a brief and eager joy at the sight— the morning and the mist running off the lakes and the birds rising up from the shaggy orange trees. The joy didn’t come often anymore and it didn’t last long and when it passed it seemed more a part of dying than delight.”

Like Jones, the depths of joy grow deeper for Otila when she discovers the baby, if for a little while. She is filled with a wild urge to take her in, a pure excitement that acts as a salve against the specter of death.

Lavinia, her much more practical and embittered sister, warns her that they’re too old for such things. But Otila is caught up in fantasy. Things are tense. They set out to return the baby to the authorities, but along the way they get lost, no longer familiar with their surroundings. At one point they pass a rusty sign they recognize, only to find that business no longer exists.

Eventually, time gets weirder, and the old ladies and their Mercedes sputter out and end up in an orange grove.

This unraveling specifically impacts Lavinia, the sister who is unwilling to accept the baby into their lives.

“The only sounds she heard were the gentle snappings somewhere in her head of small important truths that she had got along with for years—breaking.”

This story reminds me a lot of Barry Hannah’s Mother Rooney Unscrolls the Hurt from Airships. Not only is it about a regretful older woman, but it also shares an exhilarating, muggy quality. When Rooney, an old southern woman who runs a boarding house that smells like lizards, takes a bad spill, her buried memories begin to condensate around her like sweat beads.

You might say Traveling to Pridesup has something to do with what women reckon with when they don’t have children or families of their own. But my gut tells me it's about regret more broadly, and the ecstasy and horror of circling back around towards innocence, before you return to the earth.

Overall, I think this collection of stories is actually a bit literal. It makes us consider stewardship, and the complications of taking care of the life squirming all around us.

Have you read any of these stories? Do you have feelings about Florida? I’m hoping to put out a followup to this soon on Florida Vibes, tarpon fishing, and more, since I’ve become obsessed with Key West after reading this. Stay tuned…